Prunus (Almond, Apricot, Cherry, Peach, Plum) Collections

Carolyn DeBuse, USDA-ARS National Clonal Germplasm Repository, One Shields Drive, University of California, Davis, California 95616

Gayle M. Volk, USDA-ARS National Laboratory for Genetic Resources Preservation, 1111 S. Mason St., Fort Collins, Colorado 80521

Emma Balunek, USDA-ARS National Laboratory for Genetic Resources Preservation, 1111 S. Mason St., Fort Collins, Colorado 80521

John E. Preece, USDA-ARS National Clonal Germplasm Repository, One Shields Drive, University of California, Davis, California 95616

Outline

- Introduction

- Almond collection

- Apricot collection

- Cherry collection

- Peach collection

- Plum collection

- References

- Additional information

- Acknowledgments

1. Introduction

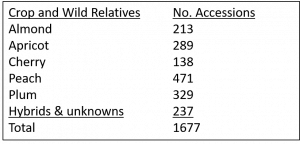

The National Clonal Germplasm Repository for Tree Fruit, Nut Crops, and Grapes in Davis, California has 1,677 unique accessions of Prunus maintained as field trees. Prunus is a genus of Rosaceae (the rose family) that includes species of the important fruit and nut crops, almond, apricot, cherry, peach, and plum. The Davis Repository collection is the most diverse Prunus collection in the U.S., representing at least 90 taxa. The USDA-ARS National Plant Germplasm System has its primary collection of 78 accessions of sour cherry (Prunus cerasus) at the Plant Genetic Resources Unit in Geneva, New York. This chapter primarily focuses on the Prunus collections in Davis, CA.

Table 1. Prunus crops in the U.S. National Plant Germplasm System collection maintained in Davis, California.

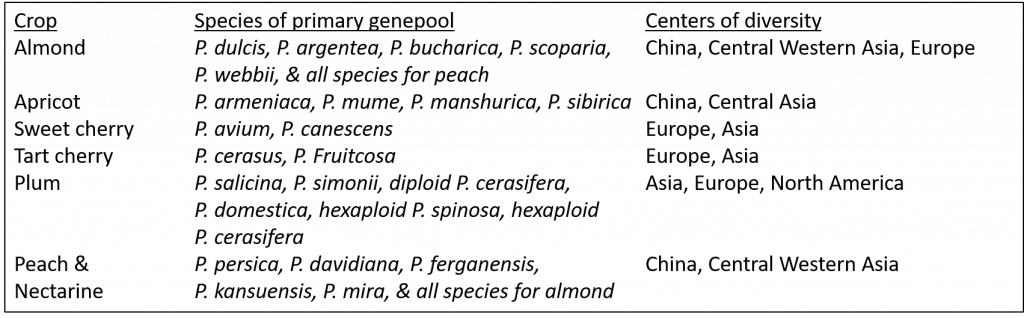

Prunus is native to countries throughout the northern hemisphere; wild species are widespread in Asia, Europe, and North America. The following centers of diversity are based on the Prunus Crop Vulnerability Statement (Prunus Crop Germplasm Committee, 2017).

Table 2. Centers of diversity for Prunus primary genepool species (from Prunus Crop Germplasm Committee, 2017).

2. almond collection

Almonds (Prunus dulcis) are native to the arid mountainous regions of Central Asia. Almonds are California’s second highest value crop, and the California almond industry generates over $21 billion in economic revenue. California produces 80% of the world’s almonds. ‘Nonpareil’ accounts for more than 50% of the almonds produced in the U.S. (Prunus Crop Germplasm Committee, 2017).

Most almond cultivars require cross-pollination to produce fruit, therefore, orchards contain multiple cultivars. Pollination is the most important factor in determining high yields. Nearly 1.6 million colonies of honey bees (more than half of American hives) travel on trucks to California at the beginning of the flower bloom period to pollinate the crop. In addition to the almonds (kernel) that are consumed as nuts, hulls are used as livestock feed and in alternative energy sources (Almond Board of California, 2016). Shelled almond production in the 2019 totaled 2.51 billion pounds on 1.18 million acres. The 2019 almond crop was valued at $6.09 billion (NASS, 2020).

The U.S. National Plant Germplasm System almond collection has 177 unique accessions that are maintained as trees in the field.

Figure 1. Almond flowers, immature almond nut (left), and mature almond nuts (right). Photo credit: John Preece (left, right), USDA Image Gallery (center).

Figure 2. Almond fruit showing the hulls that have seeds within (left) and seeds that have been removed from the shells, roasted, and salted (right). Photo credit: Gayle Volk.

Video 1. Dr. John Preece discusses the almond collection.

3. apricot collection

Apricots (Prunus armeniaca) are native to China. Before apricots were brought to North America, they were cultivated in the Mediterranean region. Apricot production was not successful in the U.S. until they were brought to California. Most apricot cultivars are self-fertile and do not require pollinizers (Jacobs and Orsi, 2020a).

Commercial apricot cultivars have a limited amount of genetic variation in adaptive traits and can be grown commercially in only a few isolated regions of the United States. As a result, apricot cultivars must be bred specifically for each region. Greater than 50% of the apricot production in California is from a few cultivars. Apricots grown for the fresh market in California and Michigan generally have one cultivar, ‘Perfection’ as a common parent (Prunus Crop Germplasm Committee, 2017). The most common apricot cultivars grown in California include ‘Patterson’ and ‘Blenheim’ for processing markets and ‘Apache’, ‘Poppy’, ‘Earlicot’, ‘Lorna’, ‘Robada’, and ‘Helena’ for fresh markets. The most common rootstocks in California are ‘Nemaguard’ and ‘Citation’ (Jacobs and Orsi, 2020a).

In 2019, United States apricot production was 9,600 acres primarily in California with a small portion grown in Washington. The total production was 51,180 tons with a total crop value of $51.4 million (NASS, 2020).

The U.S. National Plant Germplasm System apricot collection has 256 unique accessions that are maintained as trees in the field.

Figure 3. Apricot fruit in the U.S. National Plant Germplasm System. Photo credit: Gayle Volk.

Video 2. Dr. John Preece discusses the apricot collection.

4. cherry collection

Two types of cherries are produced: sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) and tart cherry (Prunus cerasus L.). ‘Bing’ accounts for 75% of the fresh market sweet cherry crop. For sweet cherry, just a few founding cultivars and their descendants have been repeatedly used as parents in North American breeding programs and this has probably led to the reduction of genetic diversity in sweet cherry. The entire tart cherry industry is based on the 400-year-old ‘Montmorency’ cultivar, which is considered an inferior cultivar in many European countries (Prunus Crop Germplasm Committee, 2017). Cherries must fully ripen on the tree because they do not continue to ripen after harvest (Haug, 2020).

Sweet cherry production is higher than tart cherry production in the United States. In 2019, the U.S. produced 757.5 million pounds of sweet cherries on 87,000 acres, mostly in California, Oregon, and Washington. Total crop value for sweet cherries was $600 million. The largest tart cherry producing state is Michigan. Tart cherries were grown on 34,100 acres and yielded 236 million pounds in 2019. Total crop value for tart cherries was $35.7 million (NASS, 2020).

The U.S. National Plant Germplasm System Prunus collections in Davis, CA have 81 accessions of Prunus avium (sweet cherry) and 25 accessions of Prunus cerasus (sour cherry) maintained as trees in the field.

Figure 4. Sweet cherry fruit in the U.S. National Plant Germplasm System. Photo credit: Gayle Volk.

Video 3. Dr. John Preece discusses the cherry collection.

5. Peach collection

Peaches and nectarines (Prunus persica) are native to China. Nectarines (Prunus persica var. nectarina) are a “fuzzless” peach and the lack of “fuzz” is caused by a recessive gene (Jacobs and Orsi, 2020b). Nectarines tend to be sweeter and more flavorful than peaches. Both peach and nectarine fruit types are separated according to the stone: clingstone, freestone, and semi-freestone. Flesh of clingstone cultivars clings to the pit of the fruit. The fruit of the clingstone cultivars is typically produced for processing and can ripen earlier in the season. Eighty percent of California’s peaches are clingstone cultivars. Freestone peaches and nectarine are usually grown for the fresh markets; flesh does not cling to the pit and they ripen later in the season. The third type of peaches and nectarines is semi-clingstone, for which the fruit flesh partially clings to the pit (Jacobs and Orsi, 2020b).

Overall, U.S. peach cultivars have a narrow genetic base, particularly compared to those from Asia. For example, peach cultivars from the eastern U.S. have a handful of commonly used parents and high levels of inbreeding. Most nectarine cultivars trace back to just four cultivars (Prunus Crop Germplasm Committee, 2017).

The United States had 74,400 acres of peach production in 2019 yielding 658,830 tons of fruit. Out of 20 states listed, California had the most acreage of peaches at 36,000 acres in 2019. South Carolina has the second most bearing acres. The value of the U.S. 2019 peach crop was $519 million. The fruit produced went to the fresh market as well as processors for canning or freezing (NASS, 2020). U.S. nectarines totaled 15,500 acres of production yielding 131,980 tons of fruit in 2019. All commercial nectarines in 2019 were grown in California (NASS, 2020).

The U.S. National Plant Germplasm System peach/nectarine collection has 459 unique accessions that are maintained as trees in the field.

Figure 5. Peach fruit in the U.S. National Plant Germplasm System. Photo credit: Gayle Volk.

Video 4. Dr. John Preece discusses the peach collection.

6. plum collection

Two species of plums are grown in California: Japanese plum (Prunus salicina) and European plum (Prunus domestica, Jacobs, 2020). Japanese plums produced in California have a high level of genetic diversity in part because Luther Burbank crossed P. salicina with other diploid plum species from the southeastern United States to increase disease resistance levels. Overall, the level of diversity of California plums is relatively low because the most common cultivars can be traced back to only a few introductions of P. salicina and one introduction of Prunus simonii from China. The prune (P. domestica) cultivar ‘French’ accounts for 96% of prune production on the West Coast. The European plum cultivar ‘Stanley’ accounts for almost all the fresh market European plum production in the eastern U.S. (Prunus Crop Germplasm Committee, 2017). Various hybrids of plum and apricot are also available on the market today.

California grew nearly all of the plums commercially produced in the United States in 2019 on 15,000 acres and yielded 97,850 tons. The value of the 2019 crop totaled $116 million (NASS, 2020).

The U.S. National Plant Germplasm System plum collection has 329 unique accessions that are maintained as trees in the field.

Figure 6. Plum fruit in the U.S. National Plant Germplasm System. Photo credit: Gayle Volk.

Video 5. Dr. John Preece discusses the plum collection.

7. references

Almond Board of California. 2016. California Almond Industry Facts. California Almonds.

Jacobs B, Orsi J. 2020a. Apricot in California. Fruit & Nut Research & Information Center. UC Davis. http://fruitandnuteducation.ucdavis.edu/fruitnutproduction/Apricot/

Jacobs B, Orsi J. 2020b. Peach & Nectarine in California. Fruit & Nut Research & Information Center. UC Davis. http://fruitandnuteducation.ucdavis.edu/fruitnutproduction/PeachNectarine/

Jacobs B. 2020. Fresh Plum. Fruit & Nut Research & Information Center. UC Davis. http://fruitandnuteducation.ucdavis.edu/fruitnutproduction/Plum/

Haug M. 2020. Cherry. Fruit & Nut Research & Information Center. UC Davis. http://fruitandnuteducation.ucdavis.edu/fruitnutproduction/Cherry/

Prunus Crop Germplasm Committee. 2017. Prunus Vulnerability Statement. https://www.ars-grin.gov/npgs/cgc_reports/prunusvuln2017.pdf

USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS). 2020. Noncitrus Fruits and Nuts 2019 Summary.

8. additional information

Curator: Rachel Spaeth, USDA-ARS National Clonal Germplasm Repository, One Shields Drive, University of California, Davis, CA 95616-8607, rachel.spaeth@usda.gov

9. Acknowledgments

Citation: DeBuse C, Volk GM, Balunek E, Preece JE. 2021. Prunus collection. In: Volk GM, Preece JE (Ed.) Field tour of the USDA National Clonal Germplasm Repository for Tree Fruit, Nut Crops, and Grapes in Davis, California. Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Date accessed. Available from: https://colostate.pressbooks.pub/davisrepositoryfieldtour/chapter/prunus-collection/

This training module was made possible in part by funding from USDA-ARS, Colorado State University, and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

Editors: Emma Balunek, Gayle Volk, Katheryn Chen

This project was funded in part by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) and USAID, and any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in such are those of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or NAS. USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this article is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the US Department of Agriculture.