Case Study: Coffee Wild Species and Cultivars

Gayle M. Volk, USDA-ARS National Laboratory for Genetic Resources Preservation, 1111 S. Mason St., Fort Collins, Colorado, 80521 (Gayle.Volk@usda.gov)

Sarada Krishnan, Global Crop Diversity Trust, Platz Der Vereinten Nationen 7, 53113 Bonn, Germany

Outline

- Introduction to coffee cultivars

- Relationships between cultivars and wild species

- Coffee conservation in genebanks

- References

- Acknowledgments

1. Introduction to coffee cultivars

Arabica coffee is 60-70% of the world coffee market. Arabica coffee beans are primarily grown in Latin America and Africa, and they are also produced in India and some other Southeast Asian countries. Arabica plants are grown at high elevations (610–1830 meters above sea level) at temperatures between 15 and 24 degrees Celsius. Most Arabica varieties are derived from “Typica” (tall cultivar from Java; large fruit and seeds) and “Bourbon” (from Ile Bourbon, now known as Reunion; broader leaves, more upright). Both cultivars are susceptible to all major pests and diseases. Arabica cultivars are self-fertile. In Central America, Arabica cultivars are threatened by coffee leaf rust (Davis et al., 2019).

Robusta coffee is 30-40% of the world coffee market and is primarily grown in Central and Western Africa, Southeast Asia, and Brazil. Robusta is primarily used for blending and for instant coffee. Robusta coffee cultivars can be grown at lower elevations at temperatures between 24 and 30 degrees Celsius. Robusta plants are more resistant to disease and parasites and have 50-60% more caffeine, compared to Arabica. Robusta cultivars are outcrossing. In Africa, Robusta cultivars are threatened by coffee wilt disease (Gibberella xylarioides) (Davis et al., 2019).

Figure 1. Robusta cultivar in Vietnam. Photo credit: Gayle Volk.

Figure 1. Robusta cultivar in Vietnam. Photo credit: Gayle Volk.

Hybrid cultivars have been created between Arabica and Robusta cultivars. The “Timor Hybrid” is resistant to coffee leaf rust. Specific cultivars resulting from the Timor hybrid include ‘Sarchimors’ (Timor Hybrid x ‘Villa Sarchi’) and ‘Catimors’ (Timor Hybrid x ‘Caturra’) (worldcoffeeresearch.org/news/2018/a-new-arabusta-for-the-21st-century).

Additional coffee cultivar information is available at the following websites:

- varieties.worldcoffeeresearch.org

- coffeeaffection.com/different-types-coffee-beans

- sca.coffee/research/coffee-plants-of-the-world

2. Relationships between coffea cultivars and wild species

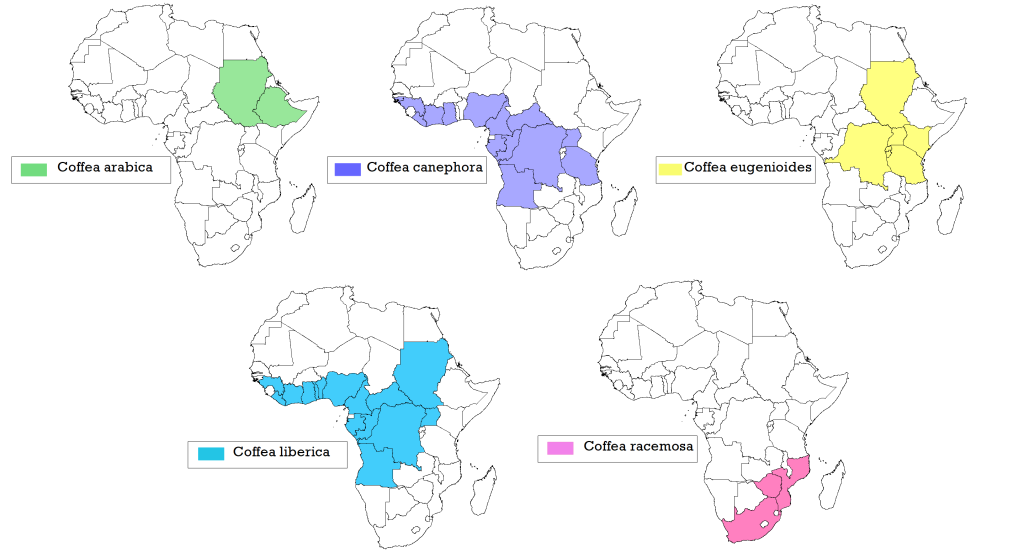

There are 124 described Coffea species, most of which are native to Africa. At the present, only a few Coffea species are locally grown or used in breeding programs.

Figure 2. Cultivated Arabica seeds (left) and wild Coffea racemosa seeds (right). Photo credit: Gayle Volk.

Figure 2. Cultivated Arabica seeds (left) and wild Coffea racemosa seeds (right). Photo credit: Gayle Volk.

Cultivated Arabica has a very low level of genetic diversity (Aerts et al., 2017). It was selected from wild Coffea arabica in Ethiopia between 500 and 1000 years ago. The primary center of diversity for C. arabica is in the highlands of southwestern Ethiopia and the Boma Plateau of South Sudan, with wild populations also reported on Mount Marsabit in Kenya (Bramel et al., 2017). In Ethiopia, wild C. arabica grows as an understory shrub and exhibits wide genotypic and phenotypic variability. The wild species are genetically distinct from Typica and Bourbon cultivars. Wild C. arabica offers genes responsible for low caffeine, higher quality specialty grade, and resistance to root nematodes and coffee berry disease (Aerts et al., 2017). The C. arabica species originated naturally through the hybridization of C. canephora and C. eugenioides.

Wild Coffea canephora is native to East Africa, including Cameroon, Central Africa Republic, Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda and northern Tanzania, and Northern Angola (Davis et al., 2006). It has often been used in breeding programs because it has resistance to coffee leaf rust (Hemileia vastatrix), coffee berry disease (caused by Colletotrichum kahawae), and root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne sp.) (Lashermes et al., 2000).

Figure 3. Coffea canephora, India. Photo credit: Sarada Krishnan.

Figure 3. Coffea canephora, India. Photo credit: Sarada Krishnan.

Coffea eugenioides is indigenous to East Africa, Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Uganda, Kenya, and western Tanzania. It is consumed locally and has a lower caffeine level than C. arabica. It is one of the parent species of C. arabica.

Coffea liberica is native to western and central Africa from Liberia to Uganda and Angola. It is cultivated and consumed locally in the Philippines and Malaysia. Fruit are larger than Coffea arabica and it is resistant to coffee rust disease.

Coffea racemosa is an indigenous coffee species in South Africa, Zimbabwe and Mozambique. It is low in caffeine and has resistance to the coffee leaf miner (Perileucoptera coffeella) (Guerreiro Filho et al., 2006). It is grown locally in Mozambique. A majority of the Madagascan Coffea species are also low in or lack caffeine.

There are many other Coffea species that have not yet been evaluated that can offer traits useful for future breeding programs to ensure sustainability of the crop.

Figure 4. Map showing countries of origin of wild Coffea species. Figure produced by Emma Balunek.

Figure 4. Map showing countries of origin of wild Coffea species. Figure produced by Emma Balunek.

Figure 5. Coffea sessiliflora, Ivory Coast. Photo credit: Sarada Krishnan.

Figure 5. Coffea sessiliflora, Ivory Coast. Photo credit: Sarada Krishnan.

Figure 6. Coffea commersoniana, Madagascar. Photo credit: Sarada Krishnan.

Figure 6. Coffea commersoniana, Madagascar. Photo credit: Sarada Krishnan.

Figure 7. Coffea neoleroyi, South Sudan. Photo credit: Sarada Krishnan.

Figure 7. Coffea neoleroyi, South Sudan. Photo credit: Sarada Krishnan.

3. Coffee conservation

Wild coffee species have desirable traits that could be incorporated into Arabica and Robusta coffee cultivars. Genebanks provide access to both cultivars and wild species for breeding programs and to determine preferred cultivars for diverse growing conditions. CATIE (The Tropical Agriculture Research and Higher Education Center) maintains the International Coffee Collection, with 2000 accessions representing 11 Coffea species originating from Africa and Central and South America (catie.ac.cr/en/unidad-agroforesteria-cafe-cacao-fe).

Coffea species are conserved in situ within reserves in Ethiopia and Uganda.

Figure 8. Wild Coffea arabica in Bonga Biosphere Reserve (in situ), Ethiopia. Photo credit: Sarada Krishnan.

Figure 8. Wild Coffea arabica in Bonga Biosphere Reserve (in situ), Ethiopia. Photo credit: Sarada Krishnan.

Collecting missions have gathered Coffea genetic resources from a number of African countries, and these materials are held in genebanks (Bramel et al., 2017). Genebanks usually maintain coffee collections as plants in the field because coffee seeds are recalcitrant and cannot be stored as seeds in cold-storage for the long-term. Cryopreservation studies have been conducted; it offers future potential as a complementary conservation strategy.

According to the Global Conservation Strategy for Coffee Genetic Resources, there are institutions with significant coffee collections in Africa (Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania), Madagascar, India and the Americas (Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica) (Bramel et al., 2017). The United States Department of Agriculture is developing a Coffea collection as part of the National Plant Germplasm System.

Genebanks around the globe have collections of C. arabica (11,415 accn.), C. canephora (625 accn.), C. liberica (94 accn.), C. eugenioides (81 accn.) and other Coffea species (7756 accn.) (Bramel et al., 2017).

4. References

Aerts R, Geeraert L, Berecha G, Hundera K, Muys B, De Kort H, Honnay O. 2017. Conserving wild Arabica coffee: Emerging threats and opportunities. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 237:75-79.

Bramel P, Krishnan S, Horna D, Lainoff B, Montagnon C. 2017. Global Conservation Strategy for Coffee Genetic Resources. Crop Trust. p. 72.

Davis AP, Chadburn H, Moat J, O’Sullivan R, Hargreaves S, Lughadha EN. 2019. High extinction risk for wild coffee species and implications for coffee sector sustainability. Science Advances 5:eaav3473.

Davis AP, Govaerts R, Bridson DM, Stoffelen P. 2006. An annotated taxonomic conspectus of the genus Coffea (Rubiaceae). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 152:465-512.

Guerreiro Filho O, et al. 2006. Coffee leaf miner resistance. Brazilian Journal of Plant Physiology. 18:109-117.

Lashermes PM, Combes C, Topart P, Graziosi G, Bertrand B, Anthony F. 2000. Molecular breeding in coffee (Coffea arabica L.). In: Sera T, Soccol CR, Pandey A, and Roussos S, (editors). Coffee Biotechnology and Quality, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Amsterdam. p. 101-112.

5. Acknowledgments

Citation: Volk GM, Krishnan S. 2020. Case Study: Coffee Wild Species and Cultivars. In: Volk GM, Byrne P (Eds.) Crop Wild Relatives in Genebanks. Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Date accessed. Available from https://colostate.pressbooks.pub/cropwildrelatives/chapter/case-study-coffee-wild-species-and-cultivars/

This training module was made possible in part by funding from USDA-ARS, Colorado State University, IICA-PROCINORTE (procinorte.net), and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

Chapter editors: Emma Balunek, Katheryn Chen, Gayle Volk

This project was funded in part by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) and USAID, and any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in such are those of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or NAS.